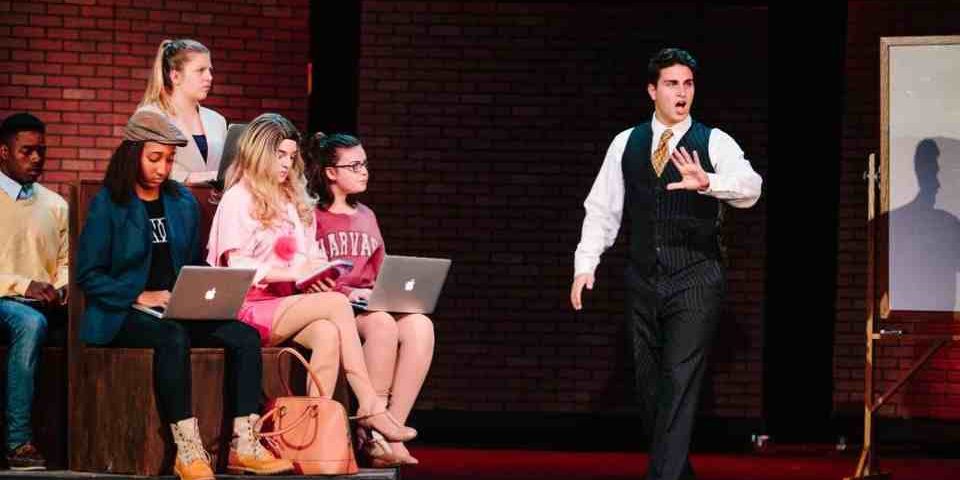

Ever since Jack Maloney played the Artful Dodger in a local children’s theater production of the musical “Oliver!” when he was 6, he knew he wanted to be a professional actor.

- 如有疑问,请联系电邮

- contact@eetcgroup.com

USNEWS:想被理想大学录取的6个建议

斯坦福大学(Stanford University, Stanford, CA)

2018年12月9日

USNEWS:从三个角度来看待SAT的写作选做题

2018年12月10日By Margaret Loftus

大学录取的标准已经程序化。比如中国,一种是单纯的依靠高考成绩,一种是依靠提前保送所需的各种荣誉证书。美国的大学录取也是标准化,提交申请信,提交各种成绩单,提交个人简历。一旦标准化,大家都会归于同质化;时间一长,招生官就会看之无味。成绩也就是几百个区间,必然会有与你相同成绩的同学申请同一所学校;申请信也是标准格式,如同查询家庭几代历史一般。唯一能够有所不同的就是“个人简历”!这也是现在很多留学咨询公司唯一能够天天在“吹嘘”的东西!好的文案,美国同行校对,这就是唯一现在能够做的。当然,事实也是如此,包括美国当地学校的同学,他们的个人简历也会拿给专职申请大学咨询的老师看一下,所以完全不需要认为这是错误的。只是要告诉大家的是,个人简历是要真实能反应你的历史,并且能够生动的展现给招生官看,这才是个人简历的本质需要。本文是USNEWS的资深教育专栏作家关于如何让学校能够录取你的建议,希望对你在申请大学时能够有所帮助!

The theater program at his school, Oxbridge Academy in West Palm Beach, Florida, was still finding its footing during his early years there, so Maloney took it upon himself to create and stage productions, including a concert of songs from the musical “Rent” and a full production of “Urinetown” that he developed out of an honors performance class. He also helped get the course into the curriculum by writing a proposal in collaboration with his theater teacher and lobbying administrators.

Now a freshman at Pennsylvania State University—University Park studying musical theater, Maloney believes that his resourcefulness – and highlighting that in his college essays – was a big factor in getting into his three top choices. The others were Northwestern University in Illinois and the University of Michigan—Ann Arbor.

He also elaborated on his experiences in interviews whenever he got the chance. “I wrote my own story,” he says, “and it was much more compelling in the end.”

College counselors have long urged high school students to find and focus on their passion. But developing it to create new opportunities for yourself and others can really grab the attention of admissions officers.

For many of them, there’s a certain sameness to the applications they read, so when prospective students carve out their own opportunities, colleges notice, says Maria Laskaris, former dean of admissions and financial aid at Dartmouth College and now a senior private counselor at Top Tier Admissions, a company focused on helping applicants navigate the admissions process. “We tell students to push beyond what the school offers,” Laskaris says.

U.S. News talked to experts to find out how to make your college application stand out.

Build on your academic strengths. Schools are looking for students who have not only done well but who have also challenged themselves, as they are more likely to succeed in college-level courses. Reviewers also take into account the level of rigor available at a particular school.

The key is to plan ahead and start in eighth or ninth grade to build a foundation that will open doors to advanced coursework later on. For instance, being ready to get advanced algebra out of the way sophomore year puts you on track to take calculus before earning that high school diploma, which might set you up better should you apply to a program that requires it, such as engineering.

Tackling honors, Advanced Placement or International Baccalaureate classes, if they’re available, shows that you’re up for the rigors of college, even if you don’t ace them.

“We’d prefer to see students challenge themselves to get a B in AP or honors courses rather than an A in a standard-level course,” says David Kaiser, the director of undergraduate enrollment management at Temple University’s Fox School of Business in Philadelphia. This shows someone who “isn’t afraid of hard work,” Kaiser says, and “it’s a better indicator of the student’s ability to perform.”

That said, it’s also important to consider carefully which advanced courses will build on your strengths – and don’t overdo it. Taking every AP option available may backfire for those who don’t excel in a particular subject, for instance, and they could see their overall GPA drop as a result.

Remember: Once you’ve been accepted, don’t slack on your studies. “Grades throughout the senior year are critical to demonstrate continued growth,” Laskaris says. “The worst students can do is take their foot off the gas.”

Get a handle on the tests. Of course, colleges have long relied on standardized tests to help them differentiate between students in a way that grades alone cannot. Increasingly, applicants are choosing to take both the SAT and the ACT.

Christoph Guttentag, dean of undergraduate admissions at Duke University in North Carolina, suggests doing just that to determine which test better suits your test-taking style. You might opt to sit for your preferred test again, but twice should be the limit, he says.

Duke, for example, accepts scores for both tests, but check with your prospective schools on their policies and whether you should submit scores for both tests. At Duke, admissions officers consider scores of individual sections from both tests, but they’ll use the highest composite score in their admissions rubric.

And what about the optional SAT essay section? While many places don’t require it, some do, and that may change year to year. Again, it’s best to consult a school’s individual policies.

More and more schools – including Bennington College in Vermont, Ohio Wesleyan University, Arizona State University—Tempeand, as of this summer, the University of Chicago – are going test-optional, meaning applicants can choose not to submit standardized-test scores for review in admissions decisions. When in doubt, check with the school’s admissions office.

Laskaris cautions students and parents to take “test-optional” with a grain of salt. “Just because those colleges are not requiring (scores) from everyone doesn’t mean 80 percent of them don’t take them,” she says. “It still does matter for many top institutions.”

Think outside your school’s extracurriculars. While Santa Monica, California, native Brendan Terry’s interest in environmental and social justice issues was first sparked in middle school, he found most of the opportunities to nurture his activist spirit off campus.

Terry interned at an educational nonprofit as a summer camp counselor for local children from low-income families and Chinese exchange students, volunteered at a community health clinic, and served as the “educational ambassador” for the 5 Gyres Institute, a Los Angeles-based nonprofit that focuses on reducing global plastic pollution, among other activities.

Now a junior majoring in chemistry at Pomona College in California, Terry is well aware of the impact of his community work on his college apps. “It was huge,” he says. “Schools always brought it up.”

Terry wrote about his activism in the majority of his essays, as well as the “activities” and “additional information” sections of the Common Application. His recommendations – one from a teacher and the other from one of the directors at 5 Gyres – reinforced his work as an activist.

No matter what your interests are, find ways to use them to make a contribution to your school or local community. Arianna Hilliard, a classmate of Maloney’s at Oxbridge Academy who is now in her first year at Vassar College in New York, was vice president of a club at her school called Race Alliance in which members met weekly to discuss the topic of race in popular culture.

To be sure, some students are too busy with a part-time job or, say, babysitting younger siblings to devote themselves to even one season of sports, much less an activity or a cause. But employment and child care are responsibilities that you can learn from, too.

“Colleges look at extracurriculars in the context of a student’s environment,” says Craig Meister, director of college counseling at Oxbridge Academy and founder of college consulting firm Admissions Intel. He urges his students to list those experiences on their apps. “It’s a combination of what you can afford and what you’re passionate about,” he says.

Consider recommendations carefully. “Always give great consideration to the people you ask to write a recommendation,” says Susan Schaurer, associate vice president for strategic enrollment management and marketing at Miami University in Ohio. Colleges vary on their preferences and typically spell that out in their application instructions.

The ideal scenario is when you can ask an instructor who taught you more than once – such as during freshman year and again later on – because then they can speak to your growth and how you might have overcome any particular challenges.

Duke, meanwhile, prefers letters from two teachers and a guidance counselor. “We find counselor recommendations so valuable in understanding the student as a member of a community,” Guttentag says.

Do a social media check. Meister implores his ninth and 10th graders to not put anything on social media or online that could be questionable. Nonetheless, he says, when looking at their info, “nine times out of 10 I find something they should take down.”

And while it’s true admissions officers don’t have time to scroll through your entire Instagram feed, they may stumble upon social media info if searching online to verify a part of your app. What’s more, it’s not unusual for schools to be alerted by alumni, community members or others to social media that paints a student in an unflattering light.

“Most institutions put a disclaimer in acceptance letters that stipulates good behavior,” Schaurer says, or they reserve the right to withdraw the offer of admission.

Meister advises students to always use appropriate language online and to scrub their social media to the extent they can of anything that doesn’t reflect the image projected in their applications. “Admission officers are savvier than ever in comparing your application persona versus your recommender’s impression of your persona versus your online persona to see if they all match up,” he says.

A good rule of thumb: “I tell them that if they wouldn’t want an admissions officer to see it, nobody else should see it online either,” Meister adds.

Show up, to the extent you’re able. Visiting the campus shows the admissions office that you’d be likely to attend if accepted. Showing up is still a great way to reveal what schools refer to as “demonstrated interest,” a factor that some 70 percent of colleges say plays at least some role in their admissions decisions, according to the National Association for College Admission Counseling.

At the same time, “most schools are attuned to resources,” Schaurer says, and “they don’t want to put students at risk who can’t afford to come for a visit.”

Making a trip to campus isn’t the only way to let your interest be known, especially in the digital age. “We count any way students engage with us,” she notes, which includes opening a college’s emails or clicking on a link in a particular message, participating in a webinar or Facebook Live event, and more.

And be sure to introduce yourself to recruiters during visits to your high school or at local college fairs, Schaurer advises. “You can show interest without leaving home.”